Quantifying Cycles in Native Knowledge Systems

In the book Black Elk Speaks, the famed Oglala Sioux medicine man explained how circles can visually represent cycles in time:

"Everything the Power of the World does is done in a circle.... Birds make their nest in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle.... The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves. Our tepees were round like the nests of birds, and these were always set in a circle, the nation's hoop"

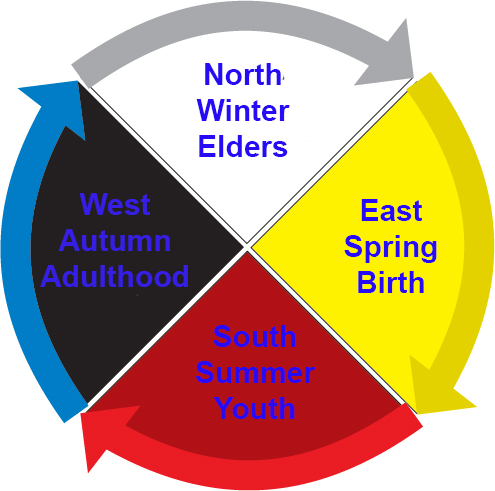

Many Native Nations used a circle called the medicine wheel to visualize this concept. The medicine wheel is divided into four quadrants. Just as Black Elk said, it can be used to symbolize repeating cycles in time: a day (morning, noon, evening, night); a year (winter, spring, summer, fall) or a lifetime (birth, youth, adulthood, elder).

One of the most important kinds of cycles for the Anishinaabe was the use of controlled burns. These help cycle nutrients back to the soil, provide more edible young shoots for humans and game animals, clear underbrush, and so on. Anishinaabe elders of the Pikangikum nation in Ontario describe how each location needed a different cycle length (what physicists call the cycle “period”). A meadow with herbal plants might need a short period, burned every 1-2 years. Bushes with berries might have an 8 to 12 year period before they need another burning. For big game like caribou, clearing a forest of the underbrush by large scale burning might happen every 30 to 50 years.

In this simulation your team is in charge of the burns for the local ecosystem. Folks back in the village will let you know if you got it right. To run the simulation, enter the periods for burns, and click the green flag.

Question: If all areas were on fire at the same time, it might overwhelm the system. How do you make sure that the fires never happen simultaneously?