Middle Passage

Like many other “Africanisms” in the new world, knowledge of African hairstyles survived the Middle Passage. Heads were often shaved upon capture, ostensibly for sanitary reasons, but with the psychological impact of being stripped of one’s culture. Re-establishing traditional hair styles in the new world was thus an act of resistance, and one that could be carried out covertly. "The enslaved that worked inside the plantation houses were required to present a neat and tidy appearance… so men and women often wore tight braids, plaits, and cornrows (made by sectioning the hair and braiding it flat to the scalp). The braid patterns were commonly based on African tradition and styles. Other styles Blacks wore proved to be an amalgam of traditional African styles, European trends, and even Native American practices" (Byrd and Tharps 2001 pp. 13-14). Historians note the variety of hairstyles described in enslaved runaway notices posted in the 1700s, and suggest that some of the more flamboyant styles were worn as outright acts of defiance. In the North, free African Americans also wore a variety of styles.

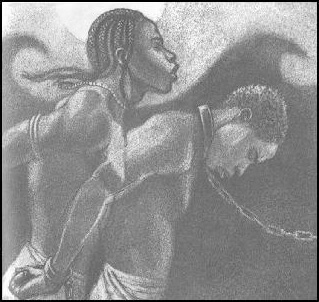

A portrait of enslaved Africans coming to America, showing clearly the cornrows they wore. Dr. Elze Bruyninx and Museum for African Art, NY.

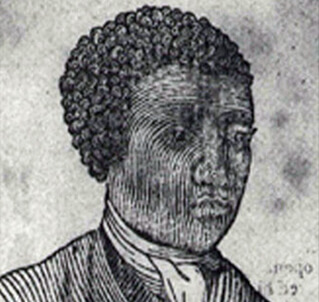

The first African American “Man of Science,” Benjamin Banneker, is shown in this etching wearing what today would be called a “natural."

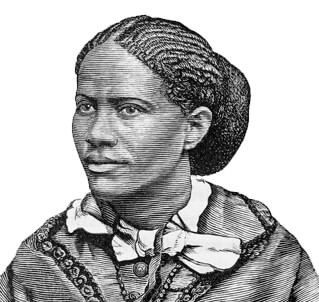

Frances Harper, whose Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892), was one of the first novels published by an African American, appears in this etching wearing what might be cornrow braids.