Four Directions Quilts

Many Indigenous cultures use the concept of Four Directions. Often it is a way to connect the physical world with some symbolic meaning. These heritage algorithms find a vertical and horizontal position (Cartesian coordinates), and then “mirror” the image (reflection symmetry). The pattern, like life, is created through balance.

The Iroquois:

The Iroquois or Haudenosaunee ("People of the Longhouse") are a confederation of six nations: the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. In their origin story, the world was originally all water. Sky Woman came down from the clouds; and to support her a giant turtle dove into the mud and brought it to the surface, creating Turtle Island (North America). From the four directions came four winds, which created the four seasons. The west wind and Sky Woman had twins, who created the rest of the world. So the Four Directions are not just compass points; they are an underlying structure of the world.

The Native nations sometimes fought. The Iroquois confederation was created to make peace. To symbolize the peace they buried weapons under a pine tree. They said the pine tree had four roots, one in each of the Four Directions, to show peace spreading everywhere . Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and others used the Iroquois confederation as an example to show the 13 colonies how they too could peacefully unite as one. We still use their eagle symbol today.

"The Tree of Peace" - Image courtesy Mohawk artist John Fadden

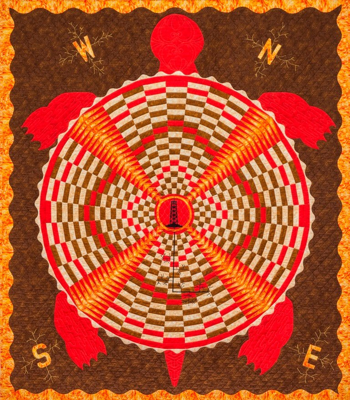

Oneida Nation artist Jackie Zalim created this quilt to raise money to send Native students to college. What does the turtle represent?

Diane Towers draws on her Oneida heritage for her quilt designs. The four colors at center represent the connections created by the four directions (seasons, color of the rising sun, etc.).

Mohawk Nation artist Carla Hemlock created this checkered pattern to represent a web connecting all of nature. Then she put oil derrick at the center, with fracture lines, to show how it is threatening nature in all directions.

Hmong:

The Hmong people trace their origins to China, but centuries ago many migrated to Southeast Asia, and tended to settle in less populated hill areas where they grew crops such as dry rice. This isolation as “hill tribes” preserved older traditions such as the shaman's trance ritual and gathering wild foods in local forests. During the 1960s, the CIA recruited them to fight against the North Vietnamese. Once the US lost the war and withdrew, over 300,000 Hmong suddenly became refugees.

While waiting in refugee camps, or resettled in the US, textile work was one of the few forms of income. According to their oral tradition, the symbols in their textiles were originally a communication system. Pandau or “flower cloth” became famous for its use of “reverse applique” (cutting spaces on the top cloth so that the one below shows through). Because quilting is a common US tradition, the Hmong symbols are sometimes stitched together as quilt blocks.

“Elephant's foot” is a symbol of prosperity.

“House” is a symbol of unity.

“Leaf frond” is a symbol of growth.

“Dragon's tail” is a symbol of power.

Celtic:

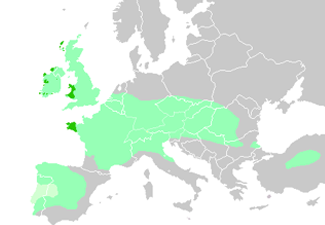

In 300 BCE the Celtic peoples were spread across Europe, including present-day Britain, Spain, France, Germany--as far east as Turkey! Today only small pockets of Celtic spoken language remain (dark green on the map). Ireland's Gaelic is the most famous. But their geometric designs-- ”Celtic Knots”-- live on. Quilt designs are one place where you can see these patterns today.

Celtic culture was once Indigenous to nearly all Europeans. You might know its designs from Tolkien's fantasy novels, Viking movies, or games like Dungeons and Dragons.

Many of the earliest examples show vines or elongated animals in interlaced curves. One theory is that the early Celtic religion believed that nature's spiritual power flowed along such paths. This shield, found in the Thames river in London, dates to about 200 BCE. Can you find the birds?

By 800 CE, Celtic interlace style was applied to a new religion in the region, Christianity. No longer stressing spirituality in nature, the patterns became more abstract. They were applied to title letters in Bibles and decorations for crosses.

Beth Ann Williams worked as a volunteer in Africa before her multiple sclerosis became too severe. She describes her attraction to Celtic quilt designs as combining her interest in heritage, nature, and religion.

This is called “true lovers knot”.

Regarding “A Celtic Celebration”, Beth Ann notes “Powerful goddesses often came in three guises, such as maiden, mother, crone. So does the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”. Can you find the 3s?

This is “Kell's Knot”. It is based on a pattern in the hand-drawn Bible in the Kells Abbey in Ireland.

Some of the patterns are created by making very simple loops and filling in the spaces, as we see in this Celtic pillow quilt.

Hawaiian:

Hawaiian quilts began with kapa moe, an Indigenous bed cover made from tree fiber cloth. Geometric designs were stamped into the cloth. Missionaries introduced western quilts, and the idea of folding cloth into quarters before cutting, so that the pattern is reflected in every quadrant. This was part of their efforts to replace “heathen” culture with their own. But the attempt backfired: Hawaiians used the new materials as a way to continue their Indigenous traditions.

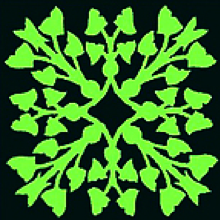

Like many Indigenous cultures, Hawaiian spiritual practices are linked to specific plants. It is traditional for anyone starting quilting to begin with this breadfruit pattern. It symbolizes a future in which the family is well fed and prosperous.

Taro also has significance for native Hawaiians: it is part of their creation story, and the most common plant in their diet. Taro gardens are sacred and are tended by the whole family.

Pressure from American plantation owners eventually forced the Hawaiian king to step down. In 1898 Hawaii was annexed as US territory. The Hawaiian flag was declared illegal, so quilters began to weave them into their fabrics in protest.

Native quilter Harriet Soong explains that this pattern shows the crown, comb and other royal symbols that traveled with princess Ka'iulani. In 1899 Ka'iulani went to Washington DC to try to convince President Cleveland to give Hawaii back to the Hawaiians.