Background 3

Statistical Designs

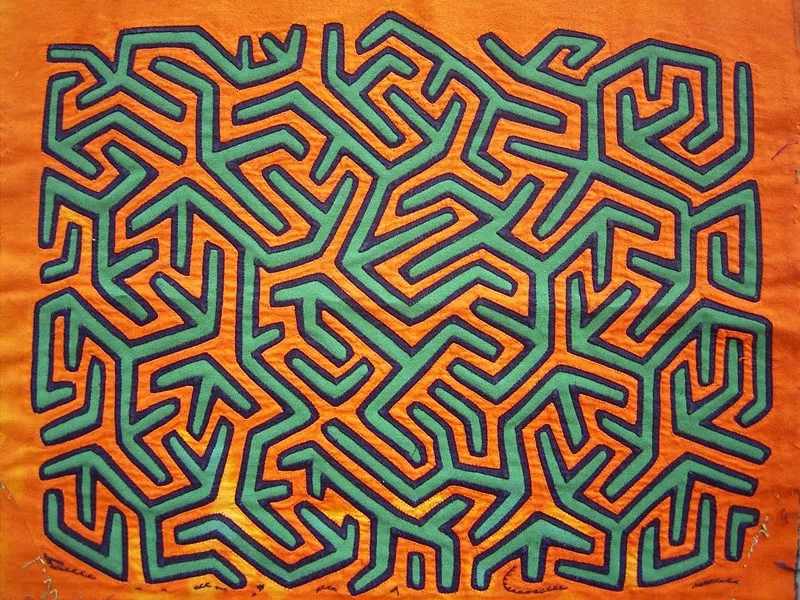

Recall that the Indigenous model had two parts: the order of algorithmic heavens, and the tangle of statistical earth. Many of the Indigenous People of Latin America used body painting to create the first images of these tangled paths. In 1681, Lionel Wafer, a British surgeon, described body painting among the Kuna people of Panama and Colombia: “They made figures of birds, beasts, men, trees, or the like, up and down every part of the body, especially the face…. The women are the painters and take great delight in it.” During colonization these images of tangled ecosystems were moved to clothing, called “molas” (originally the Kuna word for bird plumage).

The Shipibo people of Peru, Brazil and Bolivia have a similar story. The reason their designs seem to be one long path that coils up is that it represents the cosmic Anaconda, which sang the world into creation. Again these started as body painting.

We can think of these two images as expressing the tangled interconnections of people as well as nature. Hierarchical cultures like ancient Egypt were organized from the top-down, so it is no surprise that they favored the image of the pyramid. But the Kuna and Shipibo stressed trade and collaboration, so it is no surprise that they favored the bottom-up images of networks and tangled lines.

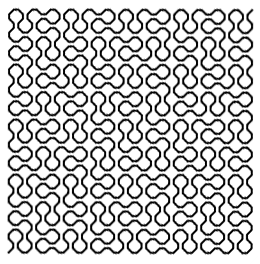

One way to model these patterns in mathematics is with a statistical model such as the “random walk”, which is used for cases such as particles diffusing through the air, or animals foraging for food. Another is the “space filling curve” such as the Peano fractal at right. Finally, there are models for network formation, such as “percolation” of water in soil, or fire in a forest.

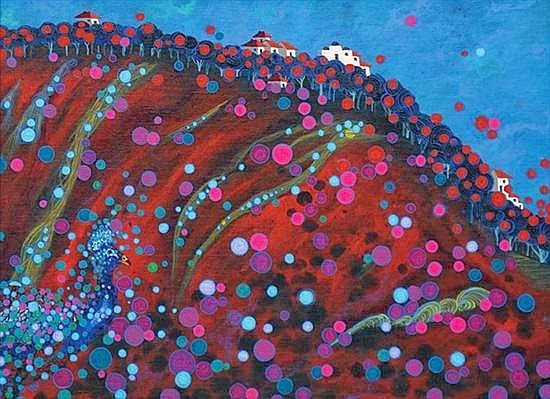

The legacy of Indigenous statistical design lives on in today’s artists. For example, Gonzalo Endara Crow (1936-1996, Bucay, Ecuador) created designs that reflect the diversity of nature. His paintings are often compared to the “magical realism” of writers such as Gabriel García Márquez.