Password:

African Architecture

The rise of computer graphics have made fractals much more common in the past 30 years, but human-made fractals existed far before the birth of computers. Anthropologists have observed that many Indigenous African socities created fractals in their architecture, textiles, sculpture, art, and religion. This was not simply unconscious or intuitive, as Africans linked these designs to concepts such as recursion and scaling.

Why did Africans focus so much on fractal designs while other groups did more with Euclidian geometry? Every culture makes use of certain geometric design themes. Native Americans, for example, made four-fold symmetry central to their designs. The African focus on fractals emphasizes their own cultural priorities. It can even be heard in their polyrhythmic music (similar simultaneous rhythms at different scales).

Logone-Birni

Palace of the chief

Path in palace

Royal insignia

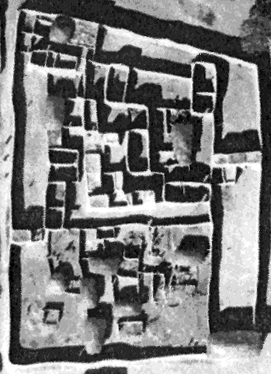

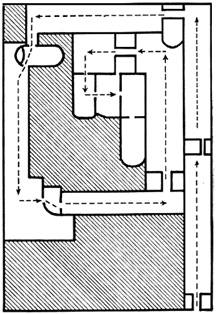

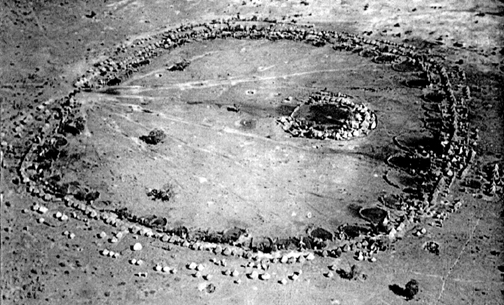

At left is an aerial photo of the place of the chief in Logone-Birni, Cameroon. The map of the path to the throne room (middle) approximates a golden spiral. The royal insignia (right) includes three iterations of scaling rectangles; they are well aware of the scaling properties of their architecture.

One way to simulate the palace is shown here: Replace exterior lines with interior lines. Another is to work in the opposite direction: grow from a small seed in the center and build walls outward. To use that simulation, select “Edit Mode” and find “Golden Rectangle” in the list of seed shapes. Which simulation do you think is better, and why?

Logone-Birni

Path in palace

Ba-ila

Ba-ila

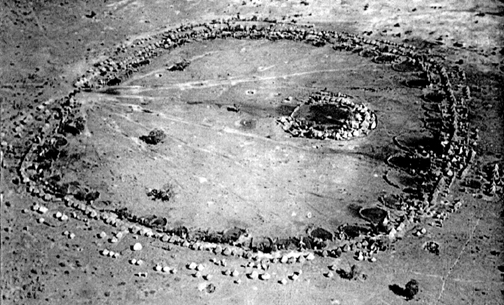

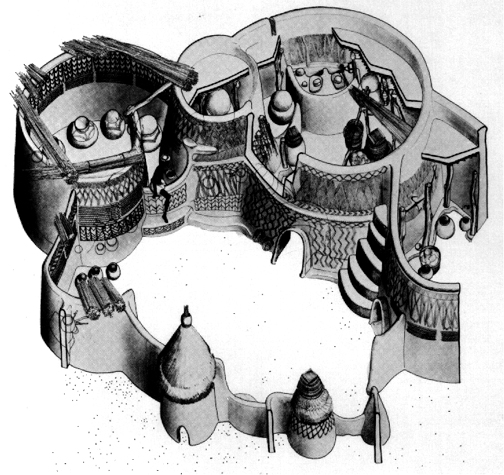

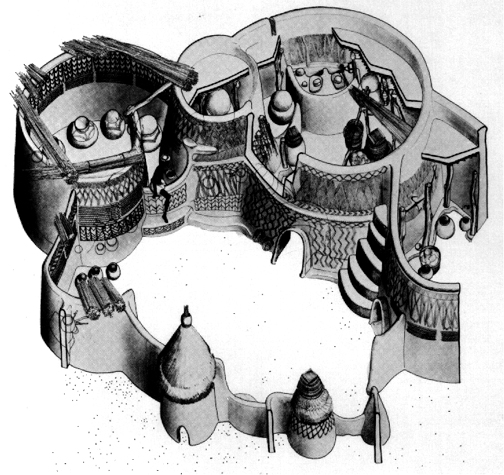

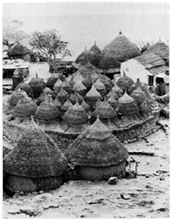

The Ba-ila settlements of Southern Zambia are enormous rings. They are made up of smaller rings, which are livestock pens (corrals). And those are made up of smaller rings which are single cylindrical houses and storage rooms. It is a ring of rings of rings. Toward the back of the village is a minature village; that of the chief's extended family. Toward the back of each coral is the family living quarters. And toward the back of each house is the sacred altar. As a logician would put it, the chief's family ring is to the whole settlement as the altar is to the house. They view this as a recurring functional role between different scales within the settlement. The chief's relation to his people is described by the word kulela, a word we would translate as 'to rule'. However it has this only as a secondary meaning— kulela is primarily to nurse and to cherish. The same word applied to a mother caring for her child, making the chief the father of the community. This relationship is echoed throughout family and spiritual ties at all scales, and is structurally mapped through self-similar architecture.

In the first iteration you see a single house. Note the single line of the sacred altar toward the back of the house. Click "2" for the second iteration. Now the altar has become the house, and it is surrounded by circular granaries forming a corral. Click "3" and you will see that the main house becomes the chief's family village, inside the village as a whole. New York architect Bernard Tsuchmi experimented with this simulation when exploring designs for a museum of African Art. See if you can adapt this shape for a contemporary building.

Why do the corrals get bigger going from the front entrance of the village to the back? This is a status gradient: the families with the most livestock will be in the back, and those with the least in the front. Why do the buildings get bigger going from the front of the corral to the back? Another status gradient: the livestock are toward the front and humans toward the back. And it is for that same reason that the altar is toward the back in the smallest scale, and the chief's family village is toward the back at the largest scale.

Ba-ila

Ba-ila

Nankani

Nankani

Zalanga

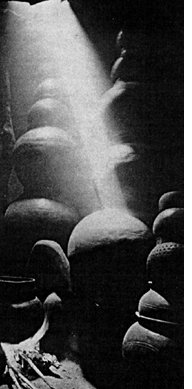

Stacks of pots in a Nankani fireplace

The homes of the Nankani are fractal series of cylinders. Here we see just one compound, a cylinder of cylinders that get smaller as you rotate counter-clockwise around the central courtyard. In this village, your life follows the architecture. Your first first rite of passage is from mother's womb to the birthing room. Your next is to crawl into the courtyard. Your next is from the courtyard to the village as a whole, and finally from the village to the world.

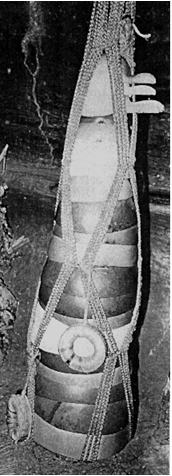

Scaling stacks of pots and bowls continue the recursion to even smaller scales. The stack of bowls is called a "zalanga", and the smallest bowl is the "kumpio", a shrine for the female head of house. When she dies, the zalanga is broken and her soul is released to eternity. While the scaling of the architecture maps life from birth to death, the zalanga models life in reverse—from the circles of the largest bowls to the tiniest holding the soul, from mature adult to the spiritual realm of ancestors who dwell in the “earth's womb.” There is a conscious scheme to the scaling circle of the Nankani: a recursion that bottoms-out at infinity, marking the passage of life and death.

Together with similar compounds, the building complex as a whole is about 20 meters; the kumpio is about 0.2 meters. How many orders of magnitude does this fractal scale across? How does this compare to the orders of magnitude in the Koch curve image? Can you change the architecture to look like the zalanga?

Nankani

Nankani

Mokoulek

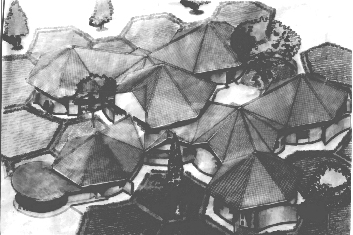

Mokoulek village plan

Photo of Mokoulek

In the Mandara Mountains of Cameroon live various ethnic groups commonly referred to as Kirdi; this particular group are the Mofou. Their buildings are created from the stone rubble that covers the Mandara mountain terrain. Much of the stone has natural fracture lines that tend to split into thick flat sheets. These ready-made bricks—along with defense needs—helped to inspire the construction of their huge castle-like complexes. But rather than the Euclidean shapes of European castles, this African architecture is fractal, with small circular granaries and larger circular granaries spiraling within three large stone enclosures, which themselves spiral from a central point (can you find the only square building?). There is a sort of recipe or algorithm that determines how the system expands to accomodate growth. It is determined by knowledge of the agricultural yield. This volume measure was then converted to a number of granaries and these were arranged in spirals. The design is not simply a matter of adding on granaries randomly, but rather the expansion of a quantitative and deliberate process.

Can you guess the purpose of the square building at center?

The square building is the village altar. It is the site of both religious and political authority; it is the location for rituals which generate cycles of agricultural fertility and ancestral succession. Again the self-generating geometic algorithm of the architecture reflects a self-generating concept of society.

Mokoulek

Mokoulek village plan

Kitwe Community Clinic

Kitwe Community Clinic

Floor Plan

African fractals continue to evolve in today's society. In Africa, they are present in professional studio art, in large-scale public art works (such as on the facade of the University of Dakar library), and even the undistinguished sellers of tourist art, who occasionally produce creations that involve fractal characteristics. In the U.S., architect Bernard Tsuchmi has experimented with the software you are using to design a modern art museum in New York City. Fractals also continue in modern African architecture. In collaboration with African American architect David Hughes, Alex Nyangula at Copperbelt University in Zambia used a fractal branching pattern to create the beautiful design above that fuses Indigenous and modern forms of African architecture.

The Kitwe design has lots of potential for expansion. But the expansion is limited if the shape intersects itself. This one itersects itself in the 5th iteration. See if you can change the design so that it will achieve higher iterations before self-intersection.

Kitwe

Floor Plan