Back to Quilt Economics and Ecology

Quilting: Recycling Made Beautiful

Reproduced from https://www.homestead.org/frugality-finance/quilting-recycling-made-beautiful/

We didn't invent recycling. Our ancestors did it by necessity. On the original homesteads across North America people re-jigged hard to obtain parts and materials and extended the life of things they needed with creative ingenuity. Nothing was wasted.

Despite our modern culture of planned redundancy, throwaways, and over consumption, recycling is finally becoming important again. However it's still largely within the venue of the system. Few are we individuals who tinker, sew, and transform things old into things once again useful. Pretty much all reconfigurations are practical and frugal, but some can be beautiful as well.

Nothing marries frugality, practicality, and beauty quite like a quilt. Handmade quilts tell stories of family, friendship, and new beginnings. Quilts were often given to travelers heading out on the long trails west during the time of the American frontier. As people started feeling the effects of the grueling trek, they lightened their loads. Treasured furniture, pianos, and fine china were left behind to litter the trail, but quilts were kept—to protect against the cold, the hard ground, and to wrap those intrepid pioneers and their families in the memories and well wishes of loved ones left behind.

The word “quilt” is derived from the Latin word “culcita”, meaning a mattress or stuffed sack. A quilt is usually considered to be made of an insulating material sandwiched between two layers of fabric. Batting has been made of many things throughout history: wool, cotton, hair, and even crumpled up nylon stockings; anything that gives the finished piece some padding. The outer layers can be multiple pieces stitched together or single cloths of linen, cotton, wool or silk. Stitching can be highly decorative, simple running stitches, or single ties positioned throughout the quilt to keep the filling from shifting.

We may never know when the first quilt was ever stitched. Fabric doesn't always preserve well, but images on monuments and statues fare better. A 5,400 year old statuette of an early Egyptian pharaoh shows the first depiction of a quilted garment.

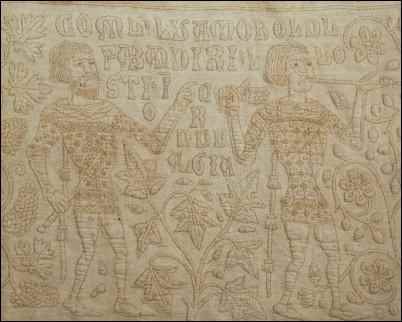

The Tristan Quilt

The Tristan Quilt, made between 1250 and 1300 AD was stitched in a pattern depicting an ancient love story. Although certainly many other quilts were made before this time, the Tristan quilt is one of the first to survive to modern times.

The first quilts were used as rugs, mattresses, and blankets, and were hung against walls, windows and doors to provide insulation and decoration. By the Middle Ages, quilted vests and caps were worn under armor for padding and even as a substitute for armor. When stuffed with layers of compressed cotton, quilting offered surprising protection against the weapons of the time.

Many people believe the modern pieced-quilt is an American invention, born during Colonial times, when women created much of what their families wore. The truth is, these early settlers had little time and resources for making piecework quilts, and the quilt-crafts they stitched were very different than the multi-colored geometric creations we're familiar with today. Before 1799, few folks had access to manufactured goods and fabric was made at home. Cotton, linen, and wool were plucked, harvested, or shorn; washed, prepared, and woven into material for everything from underwear to trousers to bedding.

When they weren't making fabrics these women were raising large broods of children, laundering (that took a whole day), doing farm chores, making butter and cheese, cooking, gardening, and preserving the harvest. Very little time would have been left for fancy needlework. Patchwork was often just that: saving as much as they could from worn out items to make patches to extend the life of newer clothing and blankets.

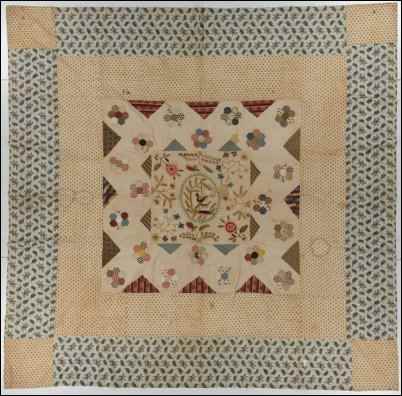

Women who could afford servants had more time for needlework and did make fancy quilts. They brought over patterns and quilting styles from the old country, which included whole-cloth bed covers, appliqués, and medallion quilts.

Medallion quilt, pre-1779

The popular medallion quilt had a central image surrounded by border rows of pieced squares. Quilts were treasures, passed from mother to daughter, and given as wedding gifts. Unfortunately, none of the earliest American quilts has survived.

According to WomenFolk.com, it wasn't until about 1840—when the North American textile industry made manufactured fabrics commonly available—that quilting became widespread. Without the need to make their own cloth, women had more time for needlework and quilting began to take on the form we are familiar with today.

The Quilting Bee

Imagine a woman living on a homestead on the prairies in the mid 1800's. Neighbors were generally miles away. Roads were often muddy and difficult to travel. Her days were filled with physically challenging chores and taking care of her large family, which included aging parents. She looked forward to Sunday when she would see her friends and neighbors at church.

Think of the quiet days before the internet, Twitter and Facebook, cell-phones and landlines, television and radio filled our every waking hour with chatter. Men's and women's worlds were very different and a woman's friends would be cherished. Isolation and loneliness were some of the challenges our female ancestors had to overcome on the frontier. Any opportunity for folks to get together was eagerly taken advantage of.

Chores are easier when done with friends and so the “bee” was born, a practical gathering where work was combined with socializing. Bees were organized around harvesting, husking corn, slaughtering animals, or building a barn. For women, who had the responsibility of keeping the home and making sure the family was clothed, having many hands available to make a quilt was invaluable. Quilting Bees were formed that not only produced quilts, but a lot of fun as well.

All winter women gathered their scraps and created their patchwork squares for their quilts, usually by lamplight in the only heated room in the house. Come spring, these women stitched their pieces together and brought down the quilting frame that was often stored against the ceiling. Neighbors from miles away would be invited to the bee, and the frame would be taken outside so that everyone could sit around it.

People arrived early in the day. Women and girls with varying degrees of creative talent and experience sat around the frame. It was an opportunity for girls to learn the essential female art of needlework. Quilting bees were also the 19th century version of social networking, introducing new people to each other, learning new skills, catching up on gossip, news, and trends. They could also be political gatherings. Women held bees to create and sell quilts to support their causes: abolition, temperance, and suffrage.

Wedding announcements were often followed by a bee, for few girls were ever married without a hope chest well stocked with quilts. Women often had patch pieces left over and trading was common. While the women sewed, the men played horseshoes or other games and got caught up with their own gossip. Come dinnertime, the hostess fed everyone, and the evening usually ended with music, dancing (and probably a jug or two).

Patterns

According to A Quilter's Complete Guide by Marianne Fons and Liz Porter, the evolution of a distinctly American patchwork and appliqué design only began during the nineteenth century. Block patterns became recognizable and somewhat standardized, and each with their own name, although these did vary by region.

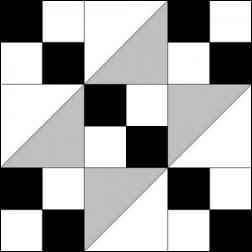

Jacob's Ladder

Although this pattern was once thought to have arisen in Colonial times when many quilts had Bible themes, and is associated with the quilts laid out to guide slaves escaping to freedom on the underground railroad, it actually first appeared at the beginning of the twentieth century. At this time, many of the popular myths surrounding quilts and their patterns were born. People realized that much of what had created American culture was passing away as modernity took hold, and a popular romantic nostalgia began to embrace (and largely recreate) history.

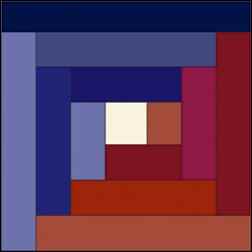

According to Barbara Brackman, a modern quilt historian and author, the Log Cabin pattern has been around a long time. However, the image of a cabin with a hearth at its centre became most popular during the great trek west in America in the middle of the 1800's. Women would make Log Cabin quilts for friends and family to keep the dream alive on the hard journey. This pattern made use of those many narrow scraps taken from around the edges of worn clothing, blankets, etc. However, since these strips were narrow and materials are of different weights, strips were laid out and stitched onto a backing. The quilt would then be tied together, rather than held with a running stitch.

Wedding Ring

This design has evolved over time, and has been known by many different names and configurations. According to HartCottageQuilts.com, the Wedding Ring may have evolved from an older 19th century design called called Pickle Dish: “By the Depression, Pickle Dish was sometimes referred to as Indian Wedding Ring, which may be how Double Wedding Ring eventually obtained its name.” The Wedding Ring design was created and became popular during the 1920's and 30's. This patch is difficult to create because of its many rounded edged pieces and intrinsic design. It is not for the beginner.

Crazy Quilt

This has to be my favorite quilting design; as easy or as complex as you wish to make it, you just can't go wrong with a crazy quilt. Another plus is these quilts can use up most of your left-overs as they are a hodge-podge of different weights and patterned fabrics. Add orphaned buttons, leftover embroidery thread and ribbon…the more the better. A great way to transform scraps into a thing of beauty.

In 1876, Americans caught their first glimpse of the crazy quilt design at the Japanese Exhibit of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. According to Cindy Brick, author of Crazy Quilts, the Japanese occasionally wore asymmetrically designed embroidered and painted kimonos that displayed their political associations, family history, animals and flowers. These bright, intricate quilt patterns were an inspiration to Americans, and the Crazy Quilt fad was born.

Since Crazy Quilts were originally used for clothing, batting was not normally used. However, as time passed, women began to simplify their embellishments and created Crazy Quilt squares that could be stitched into more serviceable, batting filled bed covers. Tie these together rather than stitch the ditch. Easy!

So, why is quilting still, and possibly even more, relevant today?

One: it's easier than ever before! Nowadays most everyone owns a sewing machine. Start with a simple design and go from there. The simplest design I know of is a patch quilt: just cut same-sized squares of any good, used fabric of similar weight without too much fuss about pattern or color. Sew them together then stitch onto batting and backing using a single tie-stitch at the corner of each square. If the material is heavy enough, you might not even need batting. Add a border and you're done! You have the added delight that you're making a quilt that was common on the first American homesteads.

Two: you're recycling! That shirt frayed beyond repair? That old beloved blanket seen better days? Those jeans can't be made into shorter shorts and still be decent? Anything too battered for the Goodwill box but that still has portions of good material can be made into a quilt. Many modern synthetics don't bleed and will retain their color for years. True, some materials are better than others, but almost everything can be adapted and recycled into quilted clothing, bedding, window insulation, or art.

Three: you're carrying on tradition! Homesteading is all about self-sustainability. Crafting your own clothes, blankets, bedding, curtains, et cetera, honors the values of your ancestors, those folks for whom the idea of “waste not, want not” was a necessity and a spiritual mantra.

Four: you're socializing! Find a quilting group or class and join up. There will be a few older women who will love the opportunity to teach you tips and techniques. These groups usually have women at various skill levels, so even the beginner will feel at home. You can create your pieces and stitch them together at home, but layering and pinning (or basting) the top, batting, and backing is a job made easier by many hands. If you're hand-quilting, they will likely have the larger frames, and you can get help with your stitching. When you do the same for others you make friends as well as quilts.

Some things to remember:

Pre-wash everything. Even “preshrunk” materials will shrink (trust me). Use hot water if you can. Wash like colors together just in case one of them bleeds. If you find a material that bleeds, try washing again till all the excess dye is gone and/or resolve to dry-clean the finished piece. This problem isn't all that common with older, recycled materials that have gone through many washes in their lifetime.

Iron everything before you cut. You want flat pieces so you can cut precision edges.

Buy/borrow/make the best tools. You can buy rotary cutters, self-healing mats, and transparent quilting rulers; they will make your project easier. But if you've got a ruler and a really good pair of sharp scissors you have what you need. I've made cardboard cutting templates that do just fine. Do spend a little on good thread to avoid knots, tangles, and the headaches that come with them. You'll need a frame, but this can be as simple as boards nailed together and the fabric pinned around the ends to secure it. Lighter projects can be piece-quilted on an embroidery hoop or ring.

Oh, yes, if you're hand stitching, get a thimble. You will need it.

Don't get complicated. You may be a natural, or you may be like the rest of us. Pick a simple design like a patch or crazy quilt and develop your skills.

Learn a little before you start. Your local library will have step-by-step instruction manuals that include patterns. Join a class or quilting group. I'm a tactile learner who needs “hands-on” to really get it, but once you have the basics you can learn a lot from the internet. YouTube videos abound with live demonstrations of every step in the process, even including how to make your own frames. If you haven't checked it out already, Google “how to quilt” and you'll find hundreds (nay, thousands!) of women eager to teach and share what they know.