Traditional Geometry

Many of the Adinkra symbols incorporate elements of transformational geometry in their design. The following pages show adinkra symbols using translation, reflection, dilation, and rotation.

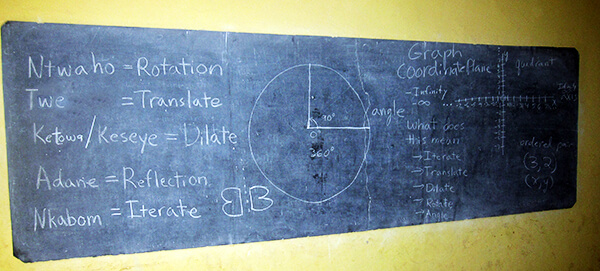

Math teachers in Kumasi, Ghana have translated these terms from English into the local language, Twi. Below is a table of these translations.

| English: | Twi: | Pronounced Like: | Literal Meaning: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | Adane | "Ah-DAWN-eh" | Reversed image |

| Dilation | Ketowa/Keseye | "KET-wah"/"ke-SEE-yah" | Smaller/larger (using both terms helps remind students that dilation can be a size change above or below 100%) |

| Rotation | Ntwaho | "En-TWA-hoe" | Spinning (for example a spinning move defines the Ntwaho dance) |

| Translation | Twe | "TWEE" | Pulling an object |

Reflection in Adinkra Symbols:

In mathematics, an image is said to have reflection when half of the the image appears to mirror across a line. For instance, the symbol to the right reflects across the X-axis, the Y-axis, and both diagonal axes. On either side of the imaginary lines, the image appears identical but opposite. This symbol is called Funtunfunefu Denkyemfunefu, or the Siamese Crocodiles. It represents democracy and unity in diversity based on the proverb, "They share one stomach and yet they fight for getting food."

Funtunfunefu Denkyemfunefu

Translation in Adinkra Symbols:

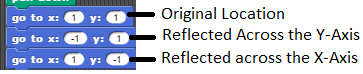

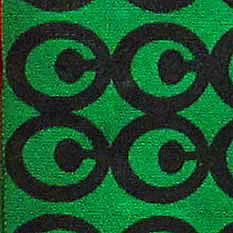

An image shows translation when it is copied and glides to a new position. We can think of the image to the right as having been created by taking one of the circles with a dot inside, and repeatedly copying and gliding until there are four. This symbol is called Ntesie - Mate Masie, or "I have heard and kept it." It represents knowledge and wisdom based on the proverb, "Deep wisdom comes out of listening and keeping what is heard." The script you would need for simulating Ntesie could be created either using the “change x by” block or the “translate by width” block. Similar blocks can create vertical translations (“change y by” block or the “translate by height”).

Ntesie - Mate Masie

Dilation in Adinkra Symbols:

In dilation you change the scale of a shape (like dilating your pupils). By repeating dilation on each copy (an "iterative loop"), we get a scaling sequence. In the image to the right, the leaves of the fern create a scaling sequence, gradually become smaller as the fern grows upwards.

This symbol is called Aya, or the fern. It represents defiance, endurance, and resourcefulness (ferns can even grow in rocky cliffs).

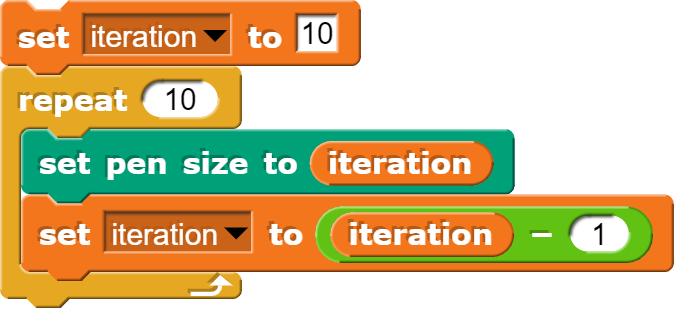

We can use the “set pen size to” command to change the size of the line you draw.

Then to get the leaf to change size every iteration, you could create a variable called "iteration" to keep track. If you were working from the bottom to the top of Aya, you would want the line to be smaller as you go, subtracting one from the iteration number each time would make the pen smaller in each iteration.

Aya

Rotation in Adinkra Symbols:

An image has rotation when it repeats at different angles around one point. For example, in the image to the right, one arm of the spiral is copied and rotated about the center point.

This symbol is called Nkontim, or the hair of the Queen's servant. It represents loyalty and service.

Nkontim

Is There an African Geometry That Is Not Part of Europe's?

One of the fascinating questions we can ask in ethnomathematics: are there some math ideas outside of those created in Europe? Consider the adinkra symbol Boa Me Na Me Mmoa Wo, which translates to "Help me and let me help you". The upper triangle is missing a square, but has an extra circle. The lower triangle is missing a circle, but has an extra square. Each has what the other needs to complete themselves. As a social symbol, the meaning is clear: mutual aid. But how do we express that relation in math? At first the word “symmetry” comes to mind, but reflection symmetry would require that each side is a mirror image; exactly the same. Here they are complements of each other, not reflections.

Let's call this new math property “mutuality”. Perhaps if colonialism never happened, Africans would have created a collection of proofs and theorems based on mutuality, just as Europe did for symmetry. We could start with a definition: two figures are said to be “mutuals” if their parts can be exchanged to create two completed wholes. There are still some details to work out (how do we define “parts”? or “completed”?). But assuming those challenges can be solved, it might open up new ways of thinking.

Can mutuals be in sets of 3 rather than pairs? In higher numbers? Could they be fractional or statistical (“figure A is an 82% mutual to figure B”)? What are the real-world applications? For example, when medical researchers study molecules, they often describe it as a “lock and key model”. We may know what a particular virus looks like, but not the shape of the molecule that can attach to its surface. Perhaps developing new forms of math based on “mutuals” could create new opportunities for medical research.