Making and Using Adinkra

Gabriel Boakye, Adinkra Artisan

Adinkra cloth is one of the traditional cloths of the Asante people. It is often worn to special occasions or ceremonies. The colors of the cloth and the symbols it features signify the message that the wearer wishes to send to the event's participants. For example, at a funeral, close family members will often wear black cloth that features symbols representing messages to the deceased.

Adinkra cloth is produced by dipping stamps into ink, and pressing them against the cloth to create a pattern. The entire process is still done by hand today: carving their own stamps, making their own ink, and stamping the fabric.

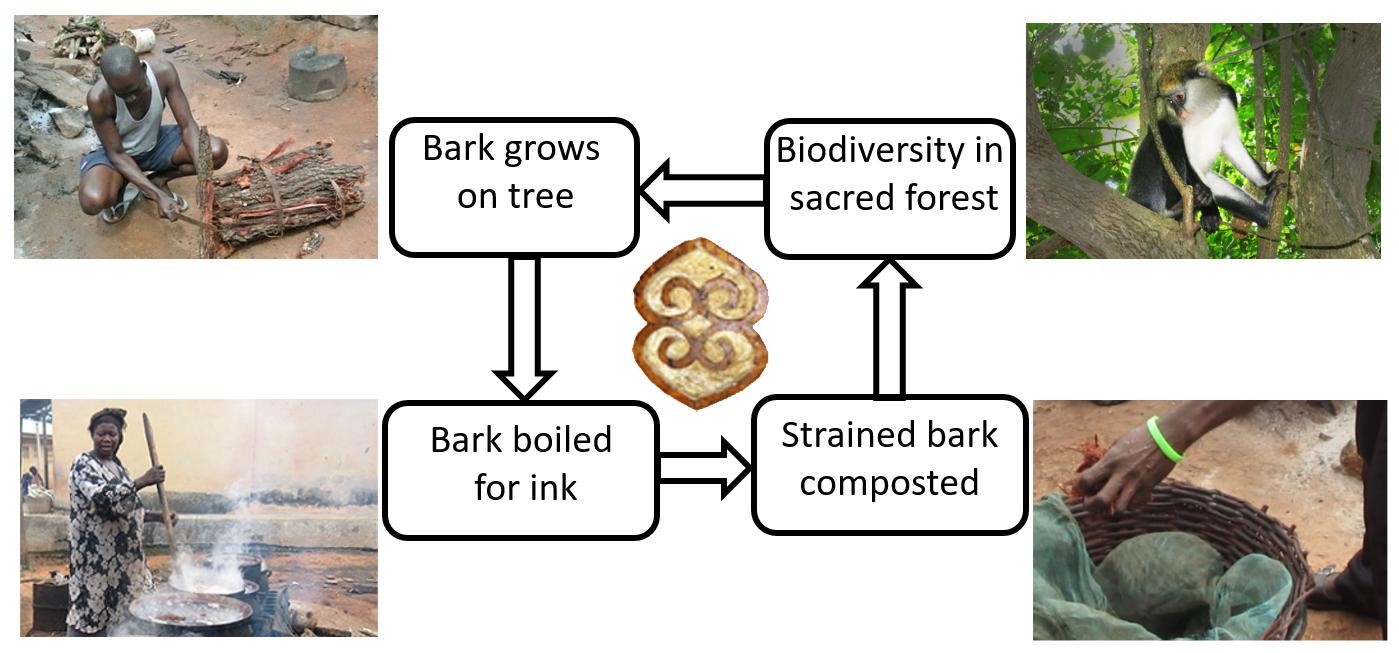

Making Ink

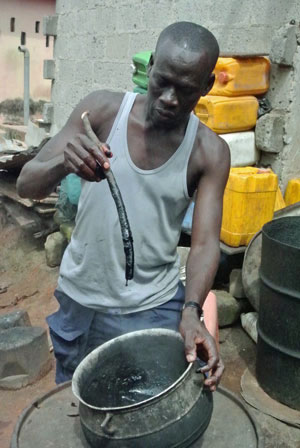

In this video, Gabriel Boakye (“Bow-ACH-aye”) shows how he uses a machete to separate out only the parts of the bark that will yield ink, and get them ready for boiling by pounding in traditional mortar and pestle (“waduro and wama”). He said they tried an electric grinder, but the bits were too small to strain out.

In this video, you can see the enormous pots of bark simmering in water over the fire. This factory is also the Baokye family home. Most of us are used to separating work and home, and struggle when they are not. But here you can see how food cooking, laundry, child care and the rest of life can exist in harmony with work life. What is the man in the blue shirt doing? Why?

Shaving the Bark

Pounding the Bark

Boiled Ink

The ink for Adinkra stamping is made from the bark of the Badie tree (Bridelia ferruginea). First, the outside bark is cut away, leaving a red fiber. Next, the red fiber is soaked in water for about 24 hours to make it soft. The soaking makes the water lightly colored; at this point it is called 'adinkra aduru' ("adinkra medicine"). It is traditionally used to treat gastric illness such as dysentery. Scientists have confirmed that it has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity.

The red fiber is then pounded to make it even softer and placed back in the water to be boiled for two days. After cooking for two days, the bark is strained out of the water, and can be used to grow mushrooms. In traditional culture little is wasted: what comes from nature is returned to nature.

With the bark removed, the liquid is boiled a final time, reducing it in volume. This final boiling produces a thick black ink for stamping.

The Importance of Asase Ye Duru

Symbol for the Divinity of Mother Earth

In many parts of Ghana, whole forests are destroyed for firewood or to make room for farming. But in areas where the Badie tree bark is harvested, the forest is protected. The bark is harvested from the trees in ways that keep the tree alive, allowing for regrowth. A single tree yields medicine, income, and environmental protection!

From this, we can see the importance of the Adinkra symbol, "Asase Ye Duru" ("the earth has weight"): it is as if humans and nature are put on opposite weighing scales that must be kept in balance.

Asase Ye Duru

Making Stamps

Adinkra symbols are carved into a calabash gourd, making stamps for printing on the cloth. Once the stamp is carved, it is attached to bamboo sticks for a grip.

Paul Boakye is Carving Stamps from a Calabash

Three Adinkra Stamps

Display of Many Adinkra Stamps

Bamboo Sticks Attached as Grip

Stamping the Adinkra Cloth

When the Adinkra Artisan is ready to stamp the fabric, a strip is laid out across a long table. The stamps are then dipped in the ink and pressed down on the cloth. The selection and arrangement of the Adinkra symbols on the cloth convey meaning to others.

Other Uses of Adinkra

In addition to stamped cloth, Adinkra symbols are used for many other purposes. Here are some examples:

Adinkra in Architecture and Advertising

The Dwennimen symbol fashioned into a Balcony.

The Gye Nyame symbol used as a restaurant name.

Bese saka symbol as ventilation pattern in concrete bricks.

Adinkra in Health Communication

In 2011, professor Audrey Bennett asked adinkra artisans if they could design a new symbol to help raise awareness of A.I.D.S. They began with the international symbol for A.I.D.S. awareness: a folded ribbon.

Paul Boakye carved the ribbon, and then added the traditional symbol for "protection", which are the dots along each side. Gabriel Boakye showed this to other artisans for approval. "One person does not make a culture," he said.

After the stamp was approved and applied to cloth, we took the results to the Suntreso Government Hospital data manager, Helena Afriyie-Siaw. Here she and Professor Bennett discuss strategies for how this traditional communication form might create new opportunities to help raise A.I.D.S. awareness.